Domestic abuse is a serious threat for many women. Often times, in the Punjabi community, the topic is never discussed or brought up because it is “taboo” and surrounded by the idea of “silence” or “Kar di ghal bhar nee dusidee” (don’t talk about family issues outside the home). This makes it difficult for Punjabi women in an abusive relationship to seek help or speak out against their situation.

Two Canadian women, Wendy Aujla & Heidi Erisman are working to bring awareness to the issue of domestic abuse in hope that it will empower women to seek help and encourage the Punjabi community to support these women.

Wendy, a doctoral candidate in sociology and Heidi an artist, joined forces to visually capture women’s experiences through art.

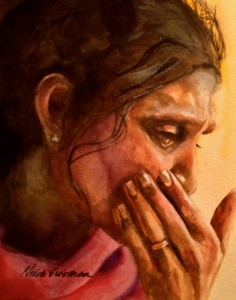

Wendy and Heidi started the project Faces of Domestic Violence, an art-research endeavor around the topic of domestic violence and the South Asian community. The goal of the project was to disseminate research findings, but also to give woman a voice; to let their story be told and heard from their perspective. They hopes Faces of Domestic Violence will raise awareness of how this is a real issue is in the South-Asian community, and should not be silenced further.

Wendy and Heidi sat down with Kaur Life to talk about their project.

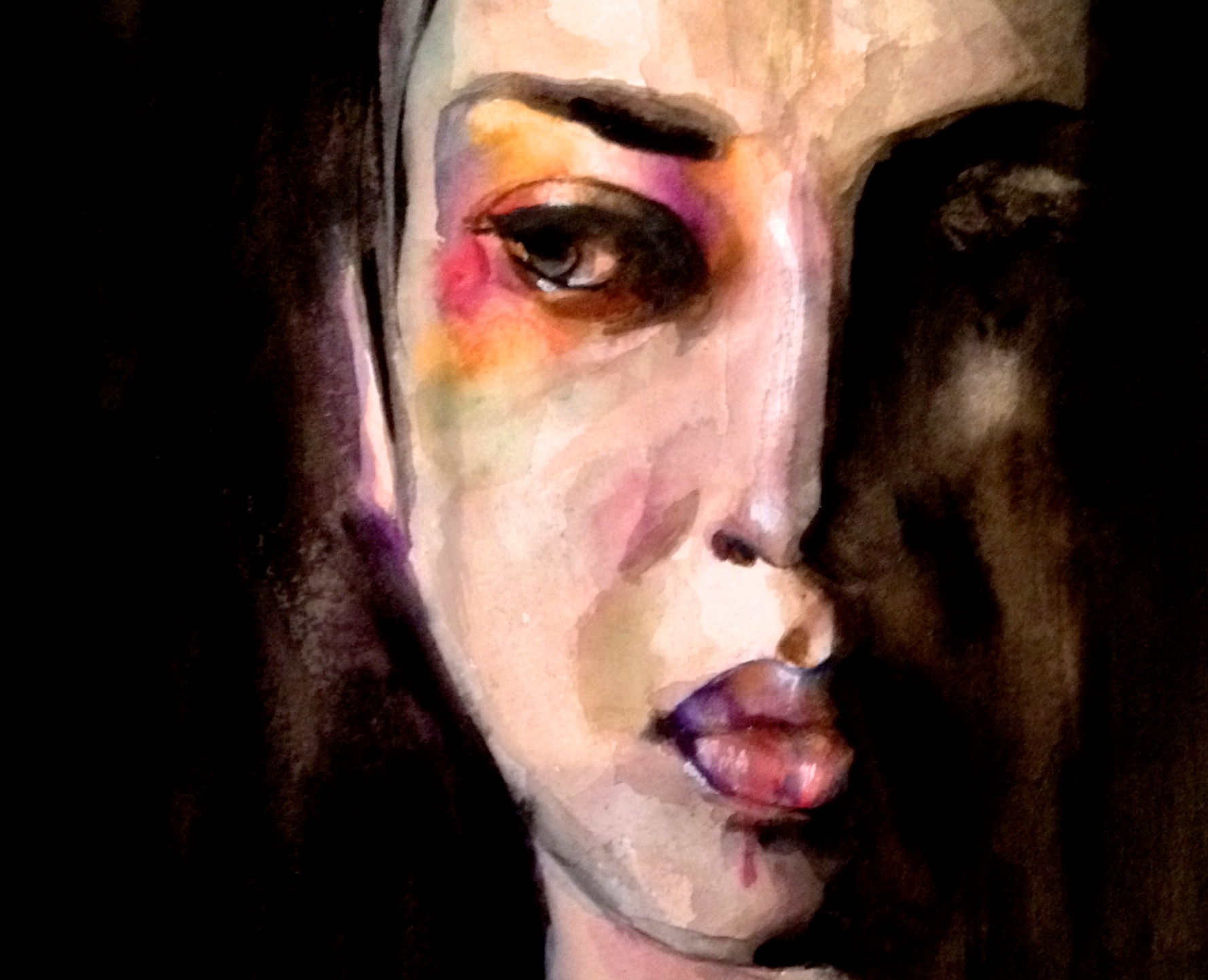

Smart & well educated but in Canada, made Jaseena prisoner in her own home. Her name is a pseudonym and the painting is an artistic rendering in order to protect her identity.

COLLABORATION

How did this collaboration come about?

Heidi: While doing her undergraduate degree, Wendy was a summer student, for two summers, at the organization where I served as executive director. I was Wendy’s supervisor there. In the context of achieving the objectives for the summer positions, I also learned more about Wendy’s emerging research interests. I was intrigued by the direction she was going and made myself available to discuss and explore her ideas. Parallel to the supervisory relationship, I also found myself looking at Wendy with an artists’ eye. That is, I saw a particular beauty in her: that of a visionary – perhaps a gentle iconoclast. Following the conclusion of her summer work, I asked Wendy if I could paint her portrait. As the older woman with lived experience, I saw a young woman with a quest and knew it wouldn’t be an easy journey. I wanted to leave her with a gift; a painting that captured her essence at that point in time, with the hopes it would inspire her when the going got tough.

Wendy: Once I completed the writing stage, I started to think about how much I admired Heidi’s art and how perhaps we could collaborate to produce something that might sneak into the homes of others where abuse is silenced. I believed Heidi’s talent for creating art was a way for us to both go on a journey where we could discover a different way of expressing the painful experiences domestic violence can be for many. I was aware of her artistic skills and excitement for painting, which could capture the feelings of the participants I spoke to. I approached Heidi with an idea and it took off from there. This will be one of many projects to come as I would like to continue to act on some of the recommendations the participants suggested. Heidi has helped guide this art-research collaboration with her spirit of creativity where others can begin to sense the feelings of the participants I spoke to. The pieces Heidi has created are impressive as they truly reflect the strength she has taken to capture the emotions of each participant.

What are the main messages, vision, mission, and goals of this collaboration?

Wendy: The first message I think is collaboration and touching others lives (as they listen to the narratives and connect with the visual paintings). No one can tackle the issue of domestic violence alone. Through this art-research initiative we are carrying forward the main message, vision and mission – to share these painful stories of domestic violence in hopes to break the silence of abuse in the South Asian community. However, this collaboration is still inclusive and can be applied to various contexts as well as to break the silence in other ethno-cultural communities.

Heidi: as an artist, my goal was to respect the anonymity of the subjects in Wendy’s study, while illustrating some of the most painful, emotional aspects of domestic violence. The paintings are not intended to endorse the suffering and alienation experienced by the women involved; rather, when paired with Wendy’s research, the paintings serve to take what has been most painful about the violence to redeem it. That is, to contemplate the art and then look for the path away from treating women as disposable instruments and move toward the place where women and men make choices to adore, respect, and care for each other.

Why did you choose visual art as a vehicle for your message?

Wendy: Visual art is a different way of connecting with people. Art seems to create an awakening experience for some, where you are able to recognize the emotions or feelings behind the images you are seeing and in this case it may break the silence of domestic violence in the South Asian community. Paintings, like the 7 women Heidi has produced from my memory of interacting with the participants, from my MA thesis, will continue to float through various communities and are accessible to deepen the experiences of those analyzing the paintings. The stories of these women are real and, at least for me, their narratives come back to life when presented or when discussed with the paintings.

Heidi: Visual art is an important vehicle in communicating messages, and in particular, when it comes to fostering transformation. In religions, for example, deities are depicted in ideal human forms that symbolize their transcendent and divine natures. In other cultures, such as the Greek and Egyptian peoples, they have used the human form to visualize beliefs about divinity, moral behaviour, and beauty. Throughout history, the function of art has been to create a focus for worship and mediation; and to guide the viewer away from their own immediate desires, transcend earthly attitudes, and to live with higher ideals. Wendy’s research and findings are raising questions about domestic violence in her culture. While endemic in all cultures, domestic violence within the South Asian community has unique features that Wendy is calling out and she is appealing for transformation. By combining her findings with visual art, Wendy is leveraging a method used for millennia by spiritual leaders, philosophers, and poets, to inspire people toward living with a more developed moral compass.

Who is the intended audience?

Wendy: Everyone, domestic violence is everyone’s business.

ABOUT THE ART

Heidi, how many paintings did you create for this project?

Heidi, how many paintings did you create for this project?

Heidi: I painted 7 paintings for this project; a portrait to reflect the emotional component of each of her participants in her study.

Heidi, what was the physical and mental process in creating these pieces?

Heidi: The process of creating the paintings was physical and mental; and the work emerged from both my conscious use of skills associated with the craft of painting, as well as drawing from my own psychological state at the time. I read Wendy’s thesis numerous times, and I also let myself draw deeply from my own memories and experiences within the South Asian community. In my minds eye, I remembered the temple visits, the Indian weddings and feasts; the vibrant saris, bangles and matching chandelier earrings. I remembered my Indian, common-law mom, in the kitchen watching over the curry chicken cooking; the card games, and the shout outs during the of cricket games. I recalled doing the Bhangra at the 1st year birthday celebrations, and the small intimate ceremonies where the newly wed bride would have her chura removed. I recalled the memories of family and a tradition, so different from my own, but welcoming, enveloping, and stimulating. And then I let myself remember how I lost it all. And with the recollection came the pain. And then I began to paint.

Heidi, what would you call this style of art?

Heidi: My art preference is classic realist painting using oil paint. I have been training at the Angel Academy of Art in Florence, IT, to master this particular method. My studies there informed how I painted these pieces, although I used watercolour instead of oil.

Heidi, what medium did you use?

Heidi: The paintings are done with watercolour on Arches watercolour paper.

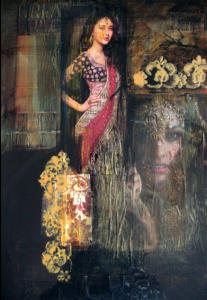

Preet. Sometimes it is the adult children who hit the hardest and hurt the deepest. Her name is a pseudonym and the painting is an artistic rendering in order to protect her identity.

Heidi, what do you see as the strengths of your pieces, visually or conceptually?

Heidi: The visual strengths I see in the pieces are that of colour, emotion, and drama. It was important for me to ensure I captured the vibrant colour often seen in the community, and those that we often associate as colours of joy and festivity. The negative emotions found in the portraits create a stark contrast to most of the colour, which in other circumstances might connote peace, harmony, fun and joy. I hoped the contrast of friendly colour with the expressions of loss, anger, pain and grief, would give voice to the paradox of the ideals for love, marriage and domestic harmony to the reality of a family member crumbling under a beautiful garments because he or she is objectified and used.

Heidi, how did you decided upon each subject’s emotions/clothing/composition/details?

Heidi: When deciding upon the subject’s emotions, I read their stories and drew upon my empathic skills. I let their stories speak to me and to move me. I imagined how I would feel if it were me. Regarding clothing, Wendy advised me about their religion, an important factor in deciding how to clothe them or cover their head.

No photos of the subjects were used. I did research and studied photos of how the hijab is worn so I could paint them with accuracy. Some of that research did influence the direction some of the paintings took. The portrait features themselves were a result of my best efforts to capture the feelings I was looking to illustrate.

Heidi, in your opinion, how can art influence social justice?

Heidi: When I think about how I may use my art to influence social justice, my goals are to create portraits and figurative paintings of people that don’t revel in the reality of how terrible things are, but that call the viewer to examine the humanity within the portraits. My ideals for art that fosters transformation personally and societally, are such that when a painting is viewed, we are made to stop and reflect; and that we are moved to do better, be better, and make choices to care for that sacred spirit that is within each person.

Heidi , In general, what inspires your art?

Heidi: People and how I experience them, inspire my art.

CONCLUSION

Harjot: She found her strength through prayer. Her name is a pseudonym and the painting is an artistic rendering in order to protect her identity.

What are your long-term goals individually? Together?

Wendy: To continue to research in this area and use creative ways with this art- research collaboration to encourage the South Asian community to address domestic violence.

What’s your next project individually? Together?

Wendy: To act on some of the recommendations that the women I interviewed shared with me. One of the many recommendations was to place something in the ethno-cultural/South Asian newspapers. Our next project, which has yet to be given a name, involves creating a visual piece that inspires those affected by domestic violence to reach out for support. This piece would be to remind the victims of domestic violence as well as the perpetrators that acts of abuse are not acceptable, nor tolerable regardless of what community you belong to. We hope to have everybody talking and more aware of what to do when they know domestic violence is happening in either their own home or someone else’s. Silence does no good, gossip leads its way into another person’s home, but until the actual informal (e.g. friends, family, neighbours) or formal (e.g. service providers) reporting of domestic violence occurs there is no end to abuse. We have been brainstorming of potential ideas (e.g. how to create the image so Heidi may begin painting the image which will be acted out by participants) since January, 2014 and also have recruited volunteers to assist us. The willingness to participate in helping create this image, so far from the volunteers has been amazing.

Do you plan to do more collaborations in the future?

Wendy: Certainly, as I mentioned before, this work will always be ongoing for me.

WENDY’S THESIS

You can learn more about Wendy’s thesis, Voicing Challenges: South Asian Immigrant Women Speak Out about their Experiences of Domestic Violence and Access to Services, here.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT

All images in this article are the exclusive property of Heidi Erisman and are protected under the United States and International Copyright laws. The images may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted or manipulated without the written permission of Heidi Erisman. All images are copyrighted © 2014 Heidi Erisman